Taiwan, a history of colonisations

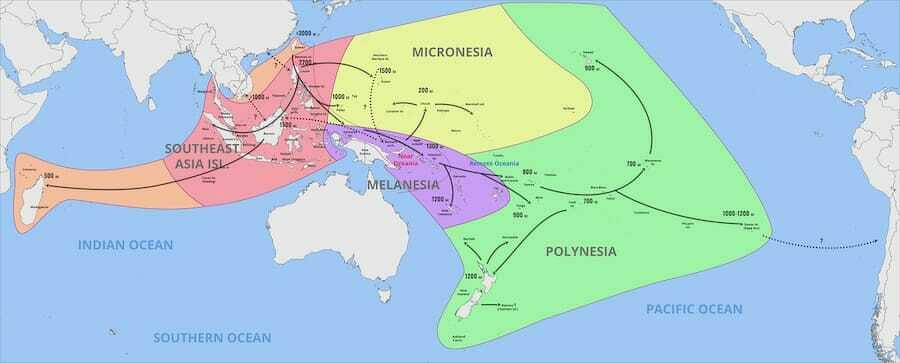

For the vast majority of its human history, Taiwan has been inhabited solely by various Austronesian peoples. There are traces of human presence dating back as far as 15'000 years ago! Taiwan is actually the cradle of the Austronesian peoples, those who today live in Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia, New Zealand and Madagascar. All these peoples and the languages they speak originated in Taiwan, from where they set out in successive waves to colonise the Pacific Ocean… and Madagascar! Today, the indigenous Austronesian peoples of Taiwan make up about 3% of the population, or about 600'000 people. The Taiwanese government currently recognises 16 groups, but in reality there are more, but the recognition process is very difficult and lengthy.

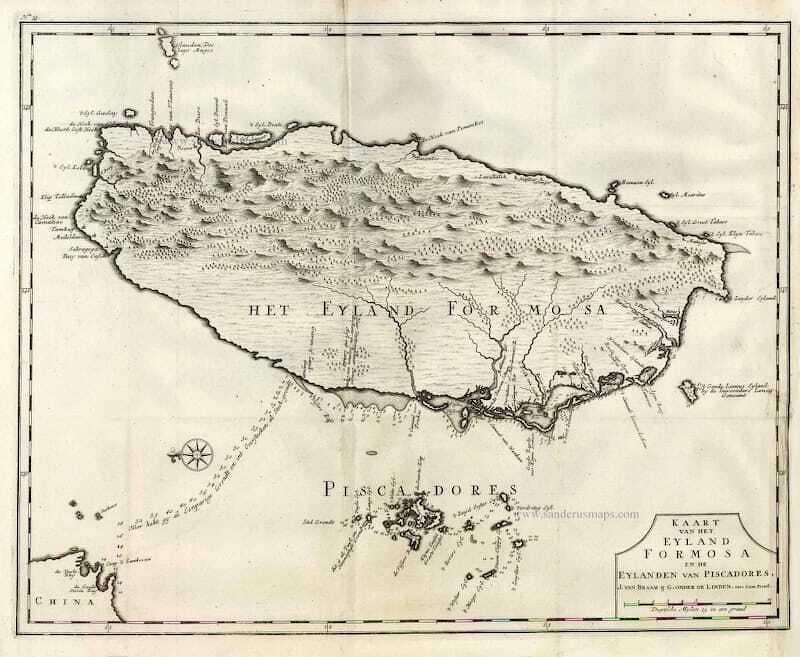

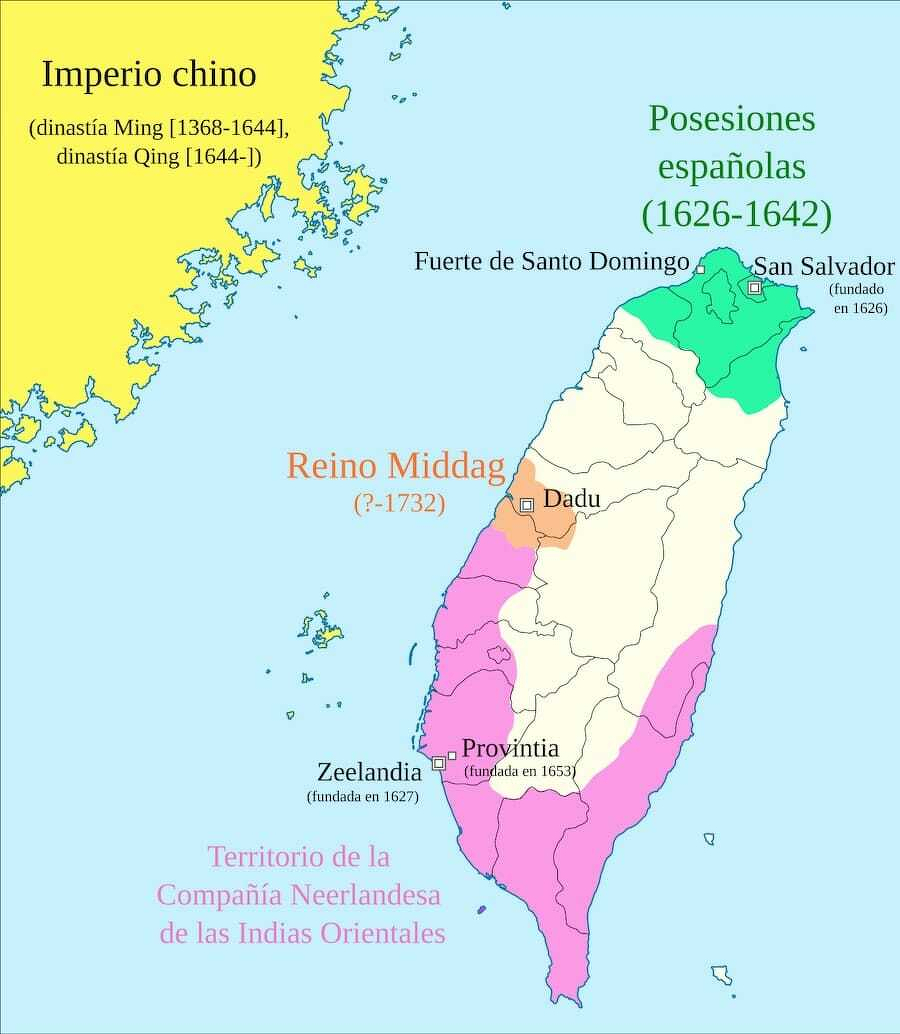

Until the 17th century, Taiwan was outside Chinese civilisation. Traditionally, Chinese imperial governments saw civilisation ending at the shores of the sea. Taiwan, in addition to being home to the Austronesian peoples mentioned above, was merely a convenient logistical base for Chinese, Japanese and Ryukyu pirates, outside the jurisdiction of any state entity. In 1624, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) began colonising the south of the island. The Dutch used Taiwan as a base for trading with China and Japan; they also traded with the indigenous people, mainly in deer skins. The Dutch also began agricultural exploitation, for which they needed labour, as the indigenous people had no interest in becoming farmers. The VOC therefore encouraged Chinese immigration to Taiwan. The VOC advertised Taiwan to the Chinese with free land and a tax-free system; sometimes they even paid the Chinese to move to Taiwan. As a result, constant streams of Chinese immigrants from Fujian and Guangdong crossed the strait and became rice and sugar farmers. It was the Dutch in the 17th century who began the Sinicisation of Taiwan. Meanwhile, there was also a small Spanish presence in the north of the island, more limited and modest than that of the Dutch. The Spanish lasted only from 1626 to 1642, when they were driven out by the Dutch, who were concerned about the presence of this inconvenient neighbour. Dutch missionaries were fairly successful in converting the indigenous populations to Christianity and were the first Westerners to study the many languages spoken on the island. When Christian missionaries returned in the 19th century (mainly Americans), they often heard stories handed down from villages that had converted to the religion of the foreigners.

Meanwhile, in China in 1644, the Ming dynasty came to an end. The Manchus, a nomadic people who lived more or less in what is now Manchuria, conquered Beijing and founded the Qing dynasty. This came as a shock to the Chinese of the time, as the Manchus were completely foreign to Chinese culture, barbarians from outside civilisation. In southern China, groups of Ming loyalists emerged, the most important of which was that of the pirate-merchant Koxinga. To secure a base from which to launch attacks on the Qing, he decided to invade Taiwan and drive out the Dutch. He succeeded. In 1661, the Dutch were expelled from Taiwan and a Chinese authority, called the Kingdom of Tungning, was established on the island for the first time. If you go to Tainan, you can see the remains of the Dutch Fort Zeelandia. The following year, however, Koxinga died. His heirs held the kingdom until 1683, when they surrendered to the Qing. The Qing very reluctantly decided to allow the western part of the island, which faces the strait and has Chinese settlements, to become part of their empire. The Manchus were even more firmly rooted on the mainland than the Chinese; they consented to precarious rule over half of the island solely to prevent the return of Western powers or Ming loyalists. In the eastern part of the island, the indigenous Austronesian populations continued their lives, unlike those in the western part, who were either assimilated by the Chinese or pushed into increasingly marginalised positions. The next two centuries are the story of the Qing trying in vain to limit Chinese immigration to Taiwan, the Chinese in Taiwan stealing land from the indigenous people, but also trade and family unions between the Chinese and the indigenous people.

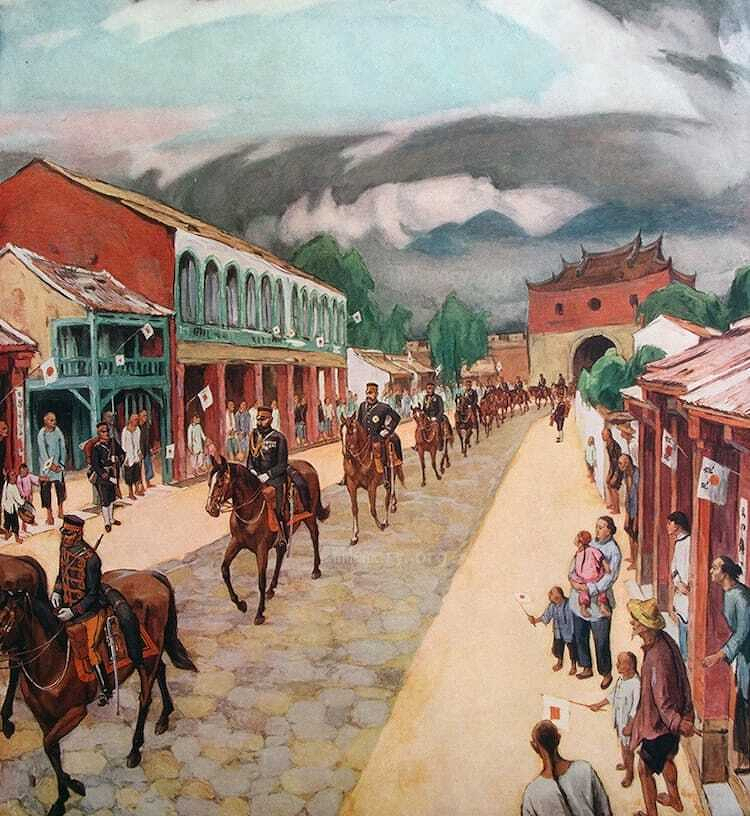

The situation in Taiwan changed completely in 1895. After two centuries of control that was more theoretical than actual, the Qing Empire ceded Taiwan to Japan after losing a war against the latter. Taiwan became Japan’s first colony. Chinese residents of Taiwan were given the choice of selling their property and leaving Taiwan by May 1897 or becoming Japanese citizens. From 1895 to 1897, it is estimated that around 6'400 people sold their property and left the island. It took the Japanese several years to pacify the island, but by around 1910 they had control of the entire territory. Under Japanese rule, for the first time in history, the entire island of Taiwan was subject to a single power. The Japanese period in Taiwan lasted 50 years and radically transformed everything, both the territory and society. The Japanese modernised Taiwan as they had modernised Japan. They built roads, railways, power stations and infrastructure; under Japan, Taiwan entered the modern age. The Japanese also modernised society, with school enrolment, for example, soaring. Of course, there was another side to the coin, namely systematic discrimination. The Taiwanese were not equal citizens; they were second-class subjects of the Japanese Empire. In Taiwan, they had no political rights, and at the beginning, there was strict segregation between the Taiwanese and the Japanese. In the second half of the colonial experience, the situation changed, with Japan now seeking the total assimilation of the Taiwanese. There was a strong focus on the Japanese language and education, changing names to Japanese, the worship of Shinto deities, etc. Despite the often harsh conditions of Japanese rule, the Taiwanese, unlike other peoples (such as the Koreans), don’t have an extremely negative view of the colonial experience as a whole. The 50 years of Japanese rule profoundly shaped Taiwanese society, and even today, the Taiwanese are probably the most Japanophile people in the world.

In 1945, Japan, which lost the Second World War, ceded Taiwan to the Republic of China, led by Chiang Kai-shek, the head of the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, KMT). Approximately 300'000 Japanese were expelled from Taiwan, and the Chinese army and administration arrived. The Chinese found a population walking around in kimonos and speaking Japanese, Taiwanese, Hakka and indigenous languages, but not Mandarin; communication was problematic. The Taiwanese went from initial joy to a bitter reality of corruption, violence, disorganisation and abuse; in practice, they found themselves moving from one colonial rule to another, but the new Chinese one was even more suffocating. In 1949, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Republic of China lost control of the whole of China, defeated by Mao’s Communists. The Republic of China retreated to Taiwan, taking with it around a million Chinese people. The period from 1945 to 1949 is the only period in history in which a Chinese state (and not an empire based in China) had authority over Taiwan. In 1949, the so-called White Terror began in Taiwan, i.e. martial law that arbitrarily repressed any form of dissent and physically eliminated an entire Taiwanese ruling and cultural class. One of the longest martial law in history, from 1949 to 1987, caused the deaths of around 20'000 people and the imprisonment of around 140'000. The KMT dictatorship in Taiwan only gradually came to an end in 1992, and in 1996, for the first time, the Taiwanese were able to elect their own president. Today, according to various international rankings, Taiwan is the freest democracy, or at least one of the freest, in the whole of Asia. For example, Taiwan was the first country in Asia to legalise same-sex marriage in 2019. Nevertheless, it can be said that Taiwan still suffers from indirect colonisation today: Taiwan is unable to free itself from the Republic of China, i.e. the regime that took refuge on the island after the Second World War. It is unable to free itself because this would mean a violent response from China. Today, the paradox is that the absurd imperialist claims of the People’s Republic of China (in China) mean that the old enemy, the Republic of China (in Taiwan), is seen as a link against Taiwan’s “independence tendencies”. There cannot be a Republic of Taiwan with a constitution centred solely on Taiwan because otherwise the Chinese Communist Party would cry secession, even though Taiwan is already, to all intents and purposes, a separate state, with a government, a parliament, an army, a currency, etc. Taiwan must live with the ambiguity of still officially calling itself the Republic of China because its bully neighbour has imperialist pretensions and does not accept the Taiwanese people’s desire to finally live in a liberal democracy that wants to remain Taiwanese.